|

| Ibsen & Grieg Palabra & Música |

Carmina Grandet

"Un amigo es una persona con la que se puede pensar en voz alta"

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson

lunes, 28 de mayo de 2012

Peer Gynt

Peer Gynt es un drama del escritor noruego Henrik Ibsen.

Fue escrito en 1867 e interpretado por primera vez en Oslo (entonces llamada Christiania) el 24 de febrero de 1876, con música incidental del compositor también noruego Edvard Grieg.

Ibsen escribió Peer Gynt viajando a Roma, Ischia y Sorrento. La obra fue publicada el 14 de noviembre de 1867, en Copenhague.

La primera edición fue de 1250 ejemplares y fue seguida, 14 días después, por una reedición de 2000 copias.

La gran cantidad de ventas se debió mayoritariamente al éxito del anterior drama de Ibsen, Brand.

A diferencia de los otros trabajos de Ibsen, Peer Gynt está escrito en verso. Originalmente iba a ser un drama escrito para ser leído, no para ser interpretado en teatro.

Las dificultades para cambiar rápidamente de escena (incluyendo un acto entero en oscuridad) ocasionaron algunos problemas en la interpretación.

A diferencia de otras obras de Ibsen, Peer Gynt es una obra fantástica, en lugar de una tragedia realista.

Fue escrito en 1867 e interpretado por primera vez en Oslo (entonces llamada Christiania) el 24 de febrero de 1876, con música incidental del compositor también noruego Edvard Grieg.

Ibsen escribió Peer Gynt viajando a Roma, Ischia y Sorrento. La obra fue publicada el 14 de noviembre de 1867, en Copenhague.

La primera edición fue de 1250 ejemplares y fue seguida, 14 días después, por una reedición de 2000 copias.

La gran cantidad de ventas se debió mayoritariamente al éxito del anterior drama de Ibsen, Brand.

A diferencia de los otros trabajos de Ibsen, Peer Gynt está escrito en verso. Originalmente iba a ser un drama escrito para ser leído, no para ser interpretado en teatro.

Las dificultades para cambiar rápidamente de escena (incluyendo un acto entero en oscuridad) ocasionaron algunos problemas en la interpretación.

A diferencia de otras obras de Ibsen, Peer Gynt es una obra fantástica, en lugar de una tragedia realista.

"En la gruta del rey de la montaña"

Edvard Grieg

"El baile de Anitra"

Edvard Grieg

Edvard Grieg

"Mañana"

Edvard Grieg

con pinturas de Igor Panov

Fors Fortuna

Fortuna era, en la mitología romana, la diosa de la suerte, buena o mala, aunque siempre se tendió a asociarla con lo bueno -lo fasto- y la fertilidad; de modo que la adversidad ha pasado a ser casi sinónimo de infortunio o "algo desafortunado".

Su alegoría solía ser la rueda de la fortuna, una especie de ruleta que significaba el azar o lo aleatorio de la buena o mala suerte; en cuanto a representación de su aspecto positivo, solía figurársele con la cornucopia.

Adjunta a Fortuna estaba la Ocasión (muchas veces confundida con la misma Fortuna), la cual se representaba casi totalmente calva, con sólo una guedeja o un mechón pequeño, ya que una buena Fortuna era entendida como de una Ocasión difícil de atrapar (como es difícil de atrapar de los cabellos a alguien calvo), en otras representaciones Fortuna aparecía figurada de un modo semejante a la Justicia: con los ojos velados o con un timón ya que pilotaba la suerte de la humanidad.

En tanto que la deidad Fortuna era casi siempre considerada fasta ("afortunada",positiva para la gente), se distinguían con adjetivos sus otros posibles aspectos: Fortuna Dubia (Fortuna Dudosa), Fortuna Brevis (Fortuna Breve) y Fortuna Mala. En lo único que coincidieron todos fue en señalar que era la diosa más caprichosa del Olimpo.

El culto a Fortuna fue introducido en Roma por Servio Tulio, teniendo en tal ciudad un templo en el Foro Boario y un santuario público en la colina del Quirinal, poseía un oráculo en Preneste y le estaban consagrados el roble -en Preneste se adjudicaba un trozo de roble a cada recién nacido, según el modo en que sucedía esto se suponía que el recién nacido tendría su fortuna, asimismo a Fortuna le estaba consagrado el día 11 de junio, durante toda esa fecha se realizaba un festival que se llamaba Fors Fortuna; se le consideraba también la propiciadora de la maternidad.

A esta deidad se le decía también Annonaria y el nombre provenía del antiguo itálico Vortumna (La que rota -hace girar- el año); no se conoce una genealogía mítica canónica o establecida de tal deidad pero se la consideraba hija de Júpiter tal como lo señala una inscripción en el santuario de Preneste y de Juno -una estatua representa a Juno dando de mamar a Fortuna-.

domingo, 27 de mayo de 2012

Oh Fortuna!

O Fortuna (poema goliardo)

O Fortuna

velut luna,

statu variabilis,

semper crescis

aut decrescis;

vita detestabilis

nunc obdurat

et tunc curat

ludo mentis aciem,

egestatem,

potestatem

dissolvit ut glaciem.

Sors immanis

et inanis,

rota tu volubilis,

status malus,

vana salus

semper dissolubilis,

obumbrata

et velata

michi quoque niteris;

nunc per ludum

dorsum nudum

fero tui sceleris.

Sors salutis

et virtutis

michi nunc contraria,

est affectus

et defectus

semper in angaria.

Hac in hora

sine mora

corde pulsum tangite;

quod per sortem

sternit fortem,

mecum omnes plangite!

Oh Fortuna,

como la luna

variable de estado,

siempre creces

o decreces;

¡Que vida tan detestable!

ahora oprimes

después alivias

como un juego,

a la pobreza

y al poder

derrites como al hielo.

Suerte monstruosa

y vacía,

tu rueda gira,

perverso,

la salud es vana

siempre se difumina,

sombrío

y velado

también a mi me mortificas;

ahora en el juego

llevo mi espalda desnuda

por tu villanía.

La Suerte en la salud

y en la virtud

está contra mí,

me empuja

y me lastra,

siempre esclavizado.

En esta hora,

sin tardanza,

toca las cuerdas vibrantes,

porque la Suerte

derriba al fuerte,

llorad todos conmigo.

Carmina Burana

El nombre de la obra Cármina burana procede del latín cármĕn -inis: ‘canto, cántico o poema’ (no confundir con la palabra árabe carmén: ‘jardín’), y burana es el adjetivo gentilicio que indica la procedencia: ‘de Bura’ (el nombre latino del pueblo alemán de Benediktbeuern). El significado del nombre es, por tanto, ‘Canciones de Beuern’.

El original Cármina burana es una colección de cantos de los siglos XII y XIII, que se han conservado en un único códice (2) encontrado en 1803 por Johann Christoph von Aretin en la abadía de Bura Sancti Benedicti (Benediktbeuern), en Baviera; en el transcurso de la secularización llegaron a la Biblioteca Estatal de Baviera en Múnich, donde se conservan (Signatura: clm 4660/4660a).

El códice recoge un total de 300 rimas, escritas en su mayoría en latín (aunque no con metro clásico), algunas partes en un dialecto del alto alemán medio, y del francés antiguo.

Fueron escritos hacia el año 1230, posiblemente en la abadía benedictina de Seckau o en el convento de Neustift, ambos en Austria.

En estos poemas se hace gala del gozo por vivir y del interés por los placeres terrenales, por el amor carnal y por el goce de la naturaleza, y con su crítica satírica a los estamentos sociales y eclesiásticos, nos dan una visión contrapuesta a la que se desarrolló en los siglos XVIII y segunda parte del XIX acerca de la Edad Media como una «época oscura».

En los Cármina burana se satirizaban y criticaban todas las clases de la sociedad en general, especialmente a las personas que ostentaban el poder en la corona y sobre todo en el clero.

Las composiciones más características son las Kontrafakturen que imitan con su ritmo las letanías del antiguo Evangelio para satirizar la decadencia de la curia romana, o para construir elogios al amor, al juego o, sobre todo, al vino, en la tradición de los cármina potoria. Por otra parte, narran hechos de las cruzadas, así como el rapto de doncellas por caballeros.

Asimismo se concentra constantemente en exaltar el destino y la suerte, junto con elementos naturales y cotidianos, incluyendo un poema largo con la descripción de varios animales.

La colección se encuentra dividida en 6 partes:

- Cármina ecclesiástica (canciones sobre temas religiosos).

- Cármina moralia et satirica (cantos morales y satíricos).

- Cármina amatoria (canciones de amor).

- Cármina potoria (contiene obras sobre la bebida, y también parodias).

- Ludi (representaciones religiosas).

- Supplemantum (versiones de todas las anteriores, con algunas variaciones)

es un poema contenido en el manuscrito Carmina Burana, creado aproximadamente entre el año 1100 y el 1200.

Está dedicado a Fortuna, diosa romana de la suerte, cuyo nombre en itálico era Vortumna, que significa "la que rueda".

Fue escrito en latín medieval sin usar la clásica métrica latina, sino un estilo del alto alemán del género Vagantenlieder, poesías de los vagabundos goliardos.

Su actual popularidad se inició con la versión de Carl Orff (1936), tocada tanto por grupos de música clásica como por artistas de otros estilos, como el caso de la agrupación Therion en su disco Deggial, o por Enigma en su disco "The screen behind the mirror", especialmente en los temas "Gravity of love" y "Modern Crusaders".

| <> | <> | ||

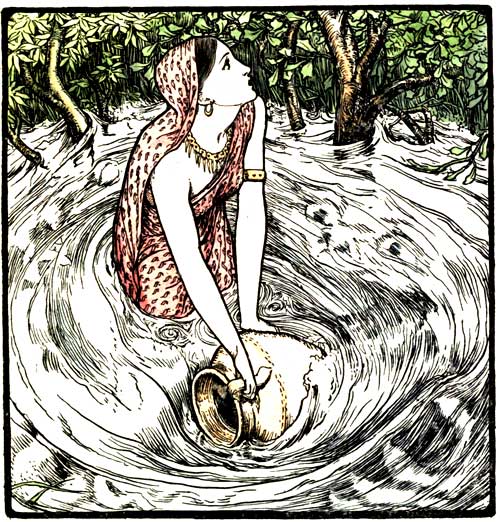

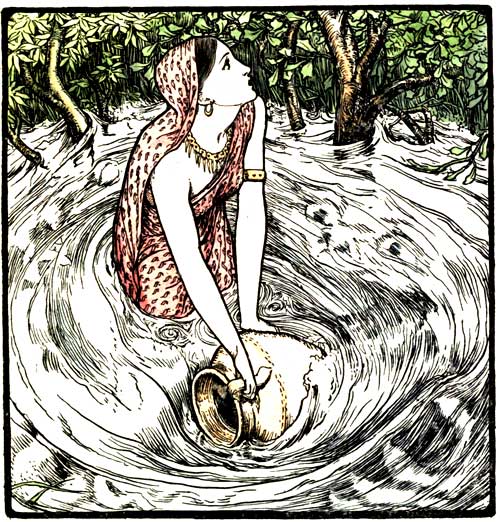

nce upon a time there lived seven brothers and a sister. The brothers were married, but their wives did not do the cooking for the family. It was done by their sister, who stopped at home to cook. The wives for this reason bore their sister-in-law much ill-will, and at length they combined together to oust her from the office of cook and general provider, so that one of themselves might obtain it. They said, "She does not go out to the fields to work, but remains quietly at home, and yet she has not the meals ready at the proper time." They then called upon their Bonga, and vowing vows unto him they secured his good-will and assistance; then they said to the Bonga, "At midday when our sister-in-law goes to bring water, cause it thus to happen, that on seeing her pitcher the water shall vanish, and again slowly re-appear. In this way she will be delayed. Let the water not flow into her pitcher, and you may keep the maiden as your own."

nce upon a time there lived seven brothers and a sister. The brothers were married, but their wives did not do the cooking for the family. It was done by their sister, who stopped at home to cook. The wives for this reason bore their sister-in-law much ill-will, and at length they combined together to oust her from the office of cook and general provider, so that one of themselves might obtain it. They said, "She does not go out to the fields to work, but remains quietly at home, and yet she has not the meals ready at the proper time." They then called upon their Bonga, and vowing vows unto him they secured his good-will and assistance; then they said to the Bonga, "At midday when our sister-in-law goes to bring water, cause it thus to happen, that on seeing her pitcher the water shall vanish, and again slowly re-appear. In this way she will be delayed. Let the water not flow into her pitcher, and you may keep the maiden as your own."

At noon when she went to bring water, it suddenly dried up before her, and she began to weep. Then after a while the water began slowly to rise. When it reached her ankles she tried to fill her pitcher, but it would not go under the water. Being frightened she began to wail and cry to her brother:

The water continued to rise until it reached her knee, when she began to wail again:

The water continued to rise until it reached her knee, when she began to wail again:

"Oh! my brother, the water reaches to my knee,Still, Oh! my brother, the pitcher will not dip."The water continued to rise, and when it reached her waist, she cried again:

The water still rose, and when it reached her neck she kept on crying:

At length the water became so deep that she felt herself drowning, then she cried aloud:

The pitcher filled with water, and along with it she sank and was drowned. The Bonga then transformed her into a Bonga like himself, and carried her off.

After a time she re-appeared as a bamboo growing on the embankment of the tank in which she had been drowned. When the bamboo had grown to an immense size, a Jogi, who was in the habit of passing that way, seeing it, said to himself, "This will make a splendid fiddle." So one day he brought an axe to cut it down; but when he was about to begin, the bamboo called out, "Do not cut at the root, cut higher up." When he lifted his axe to cut high up the stem, the bamboo cried out, "Do not cut near the top, cut at the root." When the Jogi again prepared himself to cut at the root as requested, the bamboo said, "Do not cut at the root, cut higher up;" and when he was about to cut higher up, it again called out to him, "Do not cut high up, cut at the root." The Jogi by this time felt sure that a Bonga was trying to frighten him, so becoming angry he cut down the bamboo at the root, and taking it away made a fiddle out of it. The instrument had a superior tone and delighted all who heard it. The Jogi carried it with him when he went a-begging, and through the influence of its sweet music he returned home every evening with a full wallet.

He now and then visited, when on his rounds, the house of the Bonga girl's brothers, and the strains of the fiddle affected them greatly. Some of them were moved even to tears, for the fiddle seemed to wail as one in bitter anguish. The elder brother wished to purchase it, and offered to support the Jogi for a whole year if he would consent to part with his wonderful instrument. The Jogi, however, knew its value, and refused to sell it.

It so happened that the Jogi some time after went to the house of a village chief, and after playing a tune or two on his fiddle asked for something to eat. They offered to buy his fiddle and promised a high price for it, but he refused to sell it, as his fiddle brought to him his means of livelihood. When they saw that he was not to be prevailed upon, they gave him food and a plentiful supply of liquor. Of the latter he drank so freely that he presently became intoxicated. While he was in this condition, they took away his fiddle, and substituted their own old one for it. When the Jogi recovered, he missed his instrument, and suspecting that it had been stolen asked them to return it to him. They denied having taken it, so he had to depart, leaving his fiddle behind him. The chief's son, being a musician, used to play on the Jogi's fiddle, and in his hands the music it gave forth delighted the ears of all who heard it.

When all the household were absent at their labours in the fields, the Bonga girl used to come out of the bamboo fiddle, and prepared the family meal. Having eaten her own share, she placed that of the chief's son under his bed, and covering it up to keep off the dust, re-entered the fiddle. This happening every day, the other members of the household thought that some girl friend of theirs was in this manner showing her interest in the young man, so they did not trouble themselves to find out how it came about. The young chief, however, was determined to watch, and see which of his girl friends was so attentive to his comfort. He said in his own mind, "I will catch her to-day, and give her a sound beating; she is causing me to be ashamed before the others." So saying, he hid himself in a corner in a pile of firewood. In a short time the girl came out of the bamboo fiddle, and began to dress her hair. Having completed her toilet, she cooked the meal of rice as usual, and having eaten some herself, she placed the young man's portion under his bed, as before, and was about to enter the fiddle again, when he, running out from his hiding-place, caught her in his arms. The Bonga girl exclaimed, "Fie! Fie! you may be a Dom, or you may be a Hadi of some other caste with whom I cannot marry." He said, "No. But from to-day, you and I are one." So they began lovingly to hold converse with each other. When the others returned home in the evening, they saw that she was both a human being and a Bonga, and they rejoiced exceedingly.

Now in course of time the Bonga girl's family became very poor, and her brothers on one occasion came to the chief's house on a visit.

The Bonga girl recognised them at once, but they did not know who she was. She brought them water on their arrival, and afterwards set cooked rice before them. Then sitting down near them, she began in wailing tones to upbraid them on account of the treatment she had been subjected to by their wives. She related all that had befallen her, and wound up by saying, "You must have known it all, and yet you did not interfere to save me." And that was all the revenge she took.

|

| The Project Gutenberg |

The Magic Fiddle

nce upon a time there lived seven brothers and a sister. The brothers were married, but their wives did not do the cooking for the family. It was done by their sister, who stopped at home to cook. The wives for this reason bore their sister-in-law much ill-will, and at length they combined together to oust her from the office of cook and general provider, so that one of themselves might obtain it. They said, "She does not go out to the fields to work, but remains quietly at home, and yet she has not the meals ready at the proper time." They then called upon their Bonga, and vowing vows unto him they secured his good-will and assistance; then they said to the Bonga, "At midday when our sister-in-law goes to bring water, cause it thus to happen, that on seeing her pitcher the water shall vanish, and again slowly re-appear. In this way she will be delayed. Let the water not flow into her pitcher, and you may keep the maiden as your own."

nce upon a time there lived seven brothers and a sister. The brothers were married, but their wives did not do the cooking for the family. It was done by their sister, who stopped at home to cook. The wives for this reason bore their sister-in-law much ill-will, and at length they combined together to oust her from the office of cook and general provider, so that one of themselves might obtain it. They said, "She does not go out to the fields to work, but remains quietly at home, and yet she has not the meals ready at the proper time." They then called upon their Bonga, and vowing vows unto him they secured his good-will and assistance; then they said to the Bonga, "At midday when our sister-in-law goes to bring water, cause it thus to happen, that on seeing her pitcher the water shall vanish, and again slowly re-appear. In this way she will be delayed. Let the water not flow into her pitcher, and you may keep the maiden as your own."At noon when she went to bring water, it suddenly dried up before her, and she began to weep. Then after a while the water began slowly to rise. When it reached her ankles she tried to fill her pitcher, but it would not go under the water. Being frightened she began to wail and cry to her brother:

"Oh! my brother, the water reaches to my ankles,Still, Oh! my brother, the pitcher will not dip."

"Oh! my brother, the water reaches to my knee,Still, Oh! my brother, the pitcher will not dip."The water continued to rise, and when it reached her waist, she cried again:

"Oh! my brother, the water reaches to my waist,Still, Oh! my brother, the pitcher will not dip."

"Oh! my brother, the water reaches to my neck,Still, Oh! my brother, the pitcher will not dip."

"Oh! my brother, the water measures a man's height,Oh! my brother, the pitcher begins to fill."

After a time she re-appeared as a bamboo growing on the embankment of the tank in which she had been drowned. When the bamboo had grown to an immense size, a Jogi, who was in the habit of passing that way, seeing it, said to himself, "This will make a splendid fiddle." So one day he brought an axe to cut it down; but when he was about to begin, the bamboo called out, "Do not cut at the root, cut higher up." When he lifted his axe to cut high up the stem, the bamboo cried out, "Do not cut near the top, cut at the root." When the Jogi again prepared himself to cut at the root as requested, the bamboo said, "Do not cut at the root, cut higher up;" and when he was about to cut higher up, it again called out to him, "Do not cut high up, cut at the root." The Jogi by this time felt sure that a Bonga was trying to frighten him, so becoming angry he cut down the bamboo at the root, and taking it away made a fiddle out of it. The instrument had a superior tone and delighted all who heard it. The Jogi carried it with him when he went a-begging, and through the influence of its sweet music he returned home every evening with a full wallet.

He now and then visited, when on his rounds, the house of the Bonga girl's brothers, and the strains of the fiddle affected them greatly. Some of them were moved even to tears, for the fiddle seemed to wail as one in bitter anguish. The elder brother wished to purchase it, and offered to support the Jogi for a whole year if he would consent to part with his wonderful instrument. The Jogi, however, knew its value, and refused to sell it.

It so happened that the Jogi some time after went to the house of a village chief, and after playing a tune or two on his fiddle asked for something to eat. They offered to buy his fiddle and promised a high price for it, but he refused to sell it, as his fiddle brought to him his means of livelihood. When they saw that he was not to be prevailed upon, they gave him food and a plentiful supply of liquor. Of the latter he drank so freely that he presently became intoxicated. While he was in this condition, they took away his fiddle, and substituted their own old one for it. When the Jogi recovered, he missed his instrument, and suspecting that it had been stolen asked them to return it to him. They denied having taken it, so he had to depart, leaving his fiddle behind him. The chief's son, being a musician, used to play on the Jogi's fiddle, and in his hands the music it gave forth delighted the ears of all who heard it.

When all the household were absent at their labours in the fields, the Bonga girl used to come out of the bamboo fiddle, and prepared the family meal. Having eaten her own share, she placed that of the chief's son under his bed, and covering it up to keep off the dust, re-entered the fiddle. This happening every day, the other members of the household thought that some girl friend of theirs was in this manner showing her interest in the young man, so they did not trouble themselves to find out how it came about. The young chief, however, was determined to watch, and see which of his girl friends was so attentive to his comfort. He said in his own mind, "I will catch her to-day, and give her a sound beating; she is causing me to be ashamed before the others." So saying, he hid himself in a corner in a pile of firewood. In a short time the girl came out of the bamboo fiddle, and began to dress her hair. Having completed her toilet, she cooked the meal of rice as usual, and having eaten some herself, she placed the young man's portion under his bed, as before, and was about to enter the fiddle again, when he, running out from his hiding-place, caught her in his arms. The Bonga girl exclaimed, "Fie! Fie! you may be a Dom, or you may be a Hadi of some other caste with whom I cannot marry." He said, "No. But from to-day, you and I are one." So they began lovingly to hold converse with each other. When the others returned home in the evening, they saw that she was both a human being and a Bonga, and they rejoiced exceedingly.

Now in course of time the Bonga girl's family became very poor, and her brothers on one occasion came to the chief's house on a visit.

The Bonga girl recognised them at once, but they did not know who she was. She brought them water on their arrival, and afterwards set cooked rice before them. Then sitting down near them, she began in wailing tones to upbraid them on account of the treatment she had been subjected to by their wives. She related all that had befallen her, and wound up by saying, "You must have known it all, and yet you did not interfere to save me." And that was all the revenge she took.

Las hermanas Brontë y cómo la tuberculosis acabó con las tres.

|

| Charlotte |

Charlotte Brontë, 1816-1855.

"Jane Eyre, 1847".

|

| Jane Eyre |

Emily Brontë, 1818-1848.

"Cumbres Borrascosas, 1847".

|

| Emily |

Poema de Emily Brontë (1818-1848)

Ven, camina conmigo.

Come, walk with me.

Come, walk with me.

Ven, camina conmigo,

sólo tú has bendecido alma inmortal.

Solíamos amar la noche invernal,

Vagar por la nieve sin testigos.

¿Volveremos a esos viejos placeres?

Las nubes oscuras se precipitan

ensombreciendo las montañas

igual que hace muchos años,

hasta morir sobre el salvaje horizonte

en gigantescos bloques apilados;

mientras la luz de la luna se apresura

como una sonrisa furtiva, nocturna.

Ven, camina conmigo;

no hace mucho existíamos

pero la Muerte ha robado nuestra compañía

-Como el amanecer se roba el rocío-.

Una a una llevó las gotas al vacío

hasta que sólo quedaron dos;

pero aún destellan mis sentimientos

pues en ti permanecen fijos.

No reclames mi presencia,

¿puede el amor humano ser tan verdadero?

¿puede la flor de la amistad morir primero

y revivir luego de muchos años?

No, aunque con lágrimas sean bañados,

Los túmulos cubren su tallo,

La savia vital se ha desvanecido

y el verde ya no volverá.

Más seguro que el horror final,

inevitable como las estancias subterráneas

donde habitan los muertos y sus razones,

El tiempo, implacable, separa todos los corazones.

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)